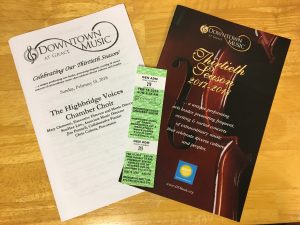

I arrived at Grace Episcopal Church in White Plains on a chilly Sunday afternoon with plenty of time to set up my video camera and microphone. I was excited to hear the progression the kids had made from rehearsals to performance. The church was formal, and the audience was an interesting mix. Though predominantly an older crowd (between 50 and 70 years old), there were some younger folks in the audience as well (between 20 and 40 years old), and the crowd was pretty evenly split racially between black and white. Though a significant amount of the students in HBV are Latino, this was not represented in the audience.  I had bought a premium ticket so that I could sit toward the front, and settled in so that I could read through the program. I found the blurb about HBV in the series’ program fascinating:

I had bought a premium ticket so that I could sit toward the front, and settled in so that I could read through the program. I found the blurb about HBV in the series’ program fascinating:

Since 1998, Highbridge Voices has been teaching children to embrace a commitment to excellence. The program provides an extraordinary training experience in choral singing to more than one hundred students in the historically underserved Highbridge neighborhood of the Bronx… (Downtown Music at Grace, 2017, p15).

The blurb continued on in this fashion talking through high school and college admission statistics, and featuring academic and personal success. I was not offended by the language, but it got me wondering if the audience, while focusing on the narrative, might project as I initially had, that they were hearing trauma in the voice. These kids sing in a variety of environments, and I’m wondering—when audiences hear these kids, especially for the first time—are they surprised?

I know that I was surprised the first time I heard them, and I looked into my surprise with some soul-searching. Were my expectations low because these kids are black and brown? Because they’re poor? Because this is a tuition-free after-school program? I have to admit with honesty, yes. These facts definitely played into my expectations. I’ve been a music teacher for 17 years. I’ve taught children from Fairfield County (most affluent in CT) to Dewey County (one of the poorest in the U.S.), and quite honestly the greatest shock for me is that this program gets 120 kids between the ages of 9-18 to sing in 10 different languages. This program gets 120 kids to sing motets, gospel, and popular music. This program gets 120 kids to sing flawlessly in 4 and 8-part harmony, in tune and in rhythm. I would be shocked if they were anyone, and impressed if they were adults, but again, I must admit that I’m additionally shocked because of the little bit that I know about their lives. Their narrative, the story of kids coming to an after-school program to pursue musical and academic excellence despite living in a traumatic environment, is a powerful narrative. Does it influence the way that the audience hears the music? In the future, I plan to interview audience members to hear their perspectives.

In his analysis of boy soprano performances, Martin Ashley works through John Cooksey’s interpretation of a boy soprano’s swansong. He investigates the idea that a boy soprano’s voice reaches its most beautiful and most powerful just before adolescence—just before it’s gone. Ashley goes through interviews and waveforms to show how the sound of the pre-pubescent male voice develops just before puberty, and yet much of the interpretation comes down to perception. He explains that the definition of a beautiful performance is inherently subjective. He also acknowledges, albeit briefly, that there’s a sense of bereavement that plays a role in this subjective perception of beauty: a preemptive mourning for what will soon be gone. It may be possible that the voice of the pre-pubescent male nearing adolescence brings present to the listener’s mind that this may be the final performance; the final swansong, and this narrative may affect the interpretation of beauty. I think narrative and perception play a role in hearing the voices of HBV as well. Though the children are talented and hard working, which I want to acknowledge and celebrate, the perception of the beauty (again, subjective) of the sound they create is linked to their narrative. Placing the music they create next to their narrative—the proximity to violence and trauma—enhances the perception of the subjective beauty of their musical performance.

These kids are phenomenal and deserve to be listened to. They deserve to both hear and create what I would subjectively label, beautiful music. In 2017 HBV performed 18 different times locally, regionally, and nationally (Making a Difference, 2018, p7). This year, 2018, they even traveled internationally on a small Canada tour. Listening is powerful and can serve as a witness to pain, political tactic, and a method of knowledge transmission. In these environments, like at the church in White Plains, was listening a political act? An act of listening asserts that the sound, message, and in this case the music, is valid and valuable. Listening’s value resides in the relationship transformation it generates between the listener and performer, a value that cannot be substituted in any other way. This connection provides a pathway for a mutual exchange of ideas and sound knowledge, similar to the exchange of information already taking place between the voice, body, and environment. This exchange during the performance of a song, followed by applause, followed by another song, creates a cycle of reciprocity or feedback loop (Kapchan, 2016). In the case of this concert, and in the case of these performances, listening becomes a political act that boldly declares: you deserve to be heard.

At the end of the concert there was a reception for the students and the attendees. This was a benefit concert, and HBV has participated in this music series at Grace Church for years. The older students are tasked with thanking attendees and introducing themselves. One boy who I’ve known for years came up to me afterward and shook my hand. “Thank you so much for being here,” he said, “It really means a lot to us.” Another girl, who had sung a solo that night joined us, thanked me for coming, and told me how nervous she’d been when she was getting ready. I complimented her and told her she didn’t seem nervous at all. At the end of our conversation they both asked, “When are you going to release that song we recorded with you?” Their narrative did not seem to affect how the students perceived their own performance. We spoke about the concert as casually as I do with any musician after a show. I wonder if by spending more time with them, the narrative is somehow playing less of a role in my own listening. Also, they don’t know it yet, but I’ll be sending them a recording of the song as a surprise in two weeks.